| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| NORTHERN

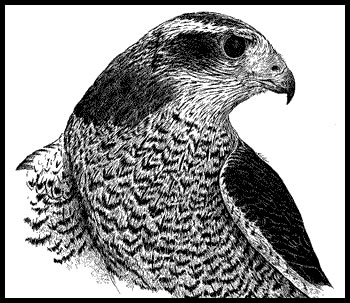

GOSHAWK |

|

During the medieval period, when falconry (the sport of hunting with a trained bird of prey) was an aristocratic pastime, the goshawk was not among the raptors favored by nobility. Aristocrats flew gyrfalcons and peregrine falcons, fast-flying birds whose dramatic, plummeting dives were as much a part of falconry's appeal as the catching of prey. The goshawk, by contrast, is a master of stealth and ambush. This efficient hunter was therefore snubbed by the upper classes. Instead it was considered appropriate for yeomen, a class of farmers who ranked below gentlemen. To these sturdy freemen, who valued results over display, the goshawk was a useful ally in the neverending concern with keeping food on the table. The goshawk earned the nickname "cook's bird" for its ability to provide game for the pot. In the U.S. settlers had other, less complimentary names for the goshawk. "Chicken hawk," "partridge hawk" and "dove hawk" were often applied to this determined hunter, who not infrequently does dine on grouse or partridge. Goshawks also hunted passenger pigeons before this once-common bird was wiped out by human overhunting. Does the goshawk eat chickens? Yes, back when farm families kept a flock of free-range chickens, goshawks did sometimes help themselves, and for good reason. Goshawks evolved in the boreal (northern) forest where life is hard and hunters must be ruthless opportunists to survive. Like other predators, goshawks routinely target the young, the weak and the disabled. A goshawk would view chickens, which fly reluctantly and poorly, as easy meals. The "Northern" element in this species' common name comes from the fact that it is primarily a bird of the northern coniferous (evergreen) forest. The word goshawk is often mispronounced as /GOSH hawk/ . It is pronounced /GOS hawk/, and comes from an Old English word that means "goose hawk." Most writers say that the bird was given that name because it frequently hunted geese, but I'm just as apt to think it's because the goshawk's finely barred chest resembles that of a domestic goose. Goshawks are the largest and most powerful of North America's three accipiters. The smallest is the sharp-shinned hawk, followed by the Cooper's hawk. Like its smaller relatives, the goshawk is a forest hawk with relatively short, rounded wings, a long rudderlike tail and long legs. Accipiters are noted for rapid acceleration (produced by those rounded wings) and agility (produced by the long tail). They sometimes track their quarry down on foot, plucking prey from cover with their long legs. All of these characteristics are true of the goshawk, but this species is much larger than the other two accipiter species found in the U.S. As a result, the goshawk can catch much larger prey and it frequently hunts mammals, while the smaller two accipiters are bird-hunting specialists. The goshawk's chief mammalian prey is chipmunks, red squirrels, rabbits and hares. Avian (bird) prey is usually medium-sized, and blue jays, grouse, ptarmigan and crows are all important menu items. Because it can hunt a wide variety of prey, the goshawk can usually (more on this later) find enough food even in winter to allow it to stay on its home territory. This species, unlike the two smaller accipiters, does not routinely migrate in large numbers, and it is not a species hawkwatchers are apt to see during the spring and fall migrations. In North America (the bird is also found in Eurasia), the breeding range of the goshawk extends from near the treeline in Alaska right across Canada to Newfoundland. In the eastern U.S. this species nests in all the New England states as well as in New York. Pennsylvania and New Jersey, extending south as far as West Virginia. In the West, the goshawk's range dips down into the mountains of California, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. The majority of goshawks stay on their home territory year-round, but the birds at the northern end of the species' breeding range do move south in the winter. At intervals, sometimes said to be every 9 or 11 years, larger numbers of goshawks leave the far northern areas. Strictly speaking, this is not a migration. This irregular, unpredictable movement is variously termed an irruption, invasion or incursion. Years when such movements occur are called flight years, and these are reported in other northern species, such as the snowy owl. The reason for this type of movement seems to be a food shortage in the winter among birds that hunt prey that undergoes cycles of population buildups and crashes. Goshawks, even those that are resident in the far northern conifer forests, can find enough to eat in the warmer months. In the brutal winter, particularly in years when prey species like snowshoe hares and ruffed grouse are at the low end of their population cycles, goshawks may have to wander south to survive. Adult North American goshawks are among the most striking of the birds of prey. (I was careful to write "North American" because the Eurasian goshawk is not as dramatically marked nor as boldly colored. It also differs from the North American goshawk in behavior, and there is some doubt as to whether the North American goshawk and the Eurasian goshawk should be considered the same species.) Male and female North American goshawks are very similar in plumage; the most obvious difference is size. Among raptors, females are almost invariably larger than their mates, and the female goshawk is no exception. Males average 19 inches in length, with a wingspan that ranges from 38 to 41 inches across. Average male weight is 29 ounces. The females average 23 inches in length, with a wingspan that ranges from 41 to 45 inches. Average female weight is 37 ounces. Adult birds are slate blue above, with a contrasting black head. And what a head! The adult North American goshawk has a blood-red eye (the Eurasian birds have yellow eyes), set off by a wide white stripe above the eye that seems to intensify the red iris color. That fierce, uncompromising glare seems to epitomize the hunting spirit of this relentless raptor. The underparts of the adults

are silver to pale bluish gray, overlaid with very fine horizontal black

bars. There are a lesser number of wider vertical black streaks, and

females typically exhibit darker, wider barring and streaking. The large

primary and secondary feathers of the wings have faint bars. The long

tail (an accipiter trademark) is a dark gray, with from 3 to 4 faint

darker stripes. Under the tail are feathers called undertail

coverts, and in the adult birds of both sexes the feathers are

pure white and soft, almost fluffy. As we will see, these specialized

feathers are used in the goshawk's courtship display. Goshawks favor woods made up of mature (full-sized) evergreen and deciduous trees (deciduous trees lose their leaves every fall; examples would be maples, birches, beeches and oaks). The hunting territory is large and vigorously defended, so goshawks do not live close together. These birds like woods broken by an avenue of open area, like a stream, a logging road or a powerline corridor. This opening is used for hunting. A hunting goshawk may simply perch on a branch and watch for the movement of prey (this method is called still-hunting), or it may dart along the open corridor, adroitly using cover to sneak up on unwary prey. Prey is dispatched with the powerful grasping toes, and then the body is carried to a "plucking post," usually a log or low branch. There it is divested of feathers or fur before being eaten, an accipiter characteristic. Goshawk nests are often reused from year to year. The adult birds winter separately and then return to their nesting territory each spring. The nest tree will be large, and in the Northeast it is often a white pine or an American beech. The stick nest is a large, flattish structure, 3 to 4 feet across. It is built in a crotch or on a large, horizontal branch near the trunk, some 30 to 40 feet up. Goshawks decorate their nests with greenery snapped off of trees; in fact, this species uses more greenery in building its nest than any other North American raptor. No one is sure what purpose is served by the greenery. My own theory is that the snapping off of branches gives the parent birds a release during a stressful time. It's a fact that the branches are torn apart with the same head action the birds use to dispatch prey. Courting starts up about one month before egg laying begins. To reestablish their pair bond after a winter apart, male and female goshawks engage in aerial displays. Both sexes circle and soar, flashing their white undertail coverts. Once the old nest is repaired or a new one is built in the same nesting territory, egg-laying begins. Each female goshawk will lay her first egg at the same time every year. In Massachusetts this may be as early as April 1st or as late as May 10th. Two or three eggs are laid, and incubation lasts 36 to 41 days. When the young are about 35 days old, they clamber out of the nest and perch on nearby branches. Now the young are called branchers, and they will return to the nest only to be fed. Male goshawks fledge (reach flying stage) when they are 35 or 36 days old. The larger females take longer, flying when they are 40 to 42 days old. Independence from their parents comes when the young are about 70 days old. Goshawks are not common birds in any part of their breeding range because of their extensive territorial requirements. However, they are more frequently found in New England now than they were 50 years ago, and in more places. As former farmland reverts back to forest, goshawks are the new landowners. In the 1950s in Massachusetts, for example, the species was rarely seen in the eastern part of the state. Now goshawks nest throughout Massachusetts, with the exception of Cape Cod and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket. In Connecticut too the birds have pushed into new areas. One place they have not colonized is the Connecticut coast, which lacks the mature forest goshawks require. It's probable that this species' population will not increase much more in either state. As we have seen, goshawks require territories of several square miles, and at a certain point, each state's carrying capacity will be filled. Because of their food and habitat choices, goshawks were not as vulnerable to pesticide poisoning back in the 1950s and 1960s as were species like the peregrine falcon and the bald eagle. Present-day population seems to be stable. The biggest challenge facing this magnificent predator is habitat fragmentation or loss as the mature forest it needs to survive and thrive is opened up for development. |